This article contains descriptions of threats of violence and mental illness.

Mississippi Remains an Outlier in Jailing People With Serious Mental Illness Without Charges

At least a dozen states have banned the practice of jailing people without charges while they await mental health treatment. But Mississippi routinely keeps people in jail during the civil commitment process.

This article was produced for ProPublica’s Local Reporting Network in partnership with Mississippi Today. It was also co-published with Sun Herald and Northeast Mississippi Daily Journal. Sign up for Dispatches to get stories like this one as soon as they are published.

Nearly 40 years ago, a federal appeals court ruled that Alabama officials could not jail people in mental health crisis who were sent to the state for help. Jailing people going through the state’s civil commitment process, the court decided, amounted to punishment. And about 30 years ago, after Kentucky was labeled the worst state in the nation for jailing mentally ill people without charges, legislators there banned it.

But a new survey of counties and an analysis of jail dockets in Mississippi, which has no such law, has found that people going through the civil commitment process for mental illness are regularly jailed as they await evaluation and treatment, even when they haven’t been charged with a crime. Some counties routinely hold such people in jail — people awaiting treatment for mental illness or substance abuse were held in jail without charges at least 2,000 times from 2019 to 2022 in 19 counties alone, sometimes for days or weeks.

Nationally, Mississippi is a stark outlier. Mississippi Today and ProPublica conducted a nationwide survey of disability advocacy organizations and state agencies that oversee behavioral health. None described anything close to the scale of what’s happening in Mississippi.

Civil commitment laws are meant to ensure people get treatment even when they don’t recognize that they need it, said James Tucker, an attorney and the director of the Alabama Disabilities Advocacy Program. Locking them up as they wait for a treatment bed doesn’t fulfill that goal.

“The bargain for your lack of freedom is that the state has decided you need treatment,” he said. “The minute that order is entered, the state has a constitutional duty to deliver treatment.”

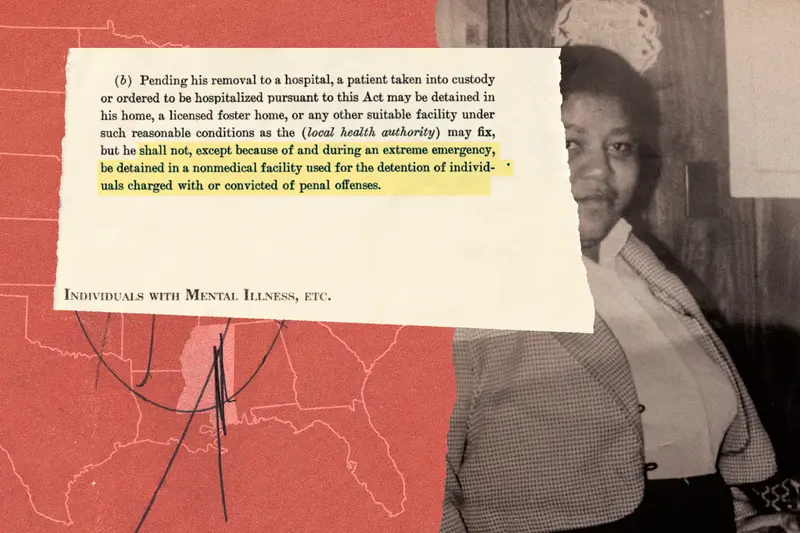

At least 12 states plus the District of Columbia prohibit jailing people undergoing commitment proceedings for mental illness unless they have been charged with a crime.

Mississippi law, however, allows people going through the civil commitment process to be sent to jail if there is “no reasonable alternative.” If there are no publicly funded beds in appropriate facilities, local officials sometimes decide they have no other option.

“We Forbid the Use of Jails”In the 1970s, a federal class-action lawsuit against Alabama officials alleged that it was unconstitutional to jail people going through the commitment process for mental illness while they awaited hearings. It was common at the time: Probate judges in three-quarters of the state’s counties had jailed people, according to discovery findings cited in a court ruling.

Lawyers for the plaintiffs — everyone in the state who had been committed or would be in the future — cited previous lawsuits that had uncovered fire hazards, overcrowding and a dearth of mental health and routine medical care in Alabama’s county jails.

The district court ruled against the plaintiffs’ constitutional claims, reasoning that if the local jail was the only option in a county, it was the least restrictive facility that would also protect society.

This article contains descriptions of threats of violence and mental illness.

This article was produced for ProPublica’s Local Reporting Network in partnership with Mississippi Today. It was also co-published with Sun Herald and Northeast Mississippi Daily Journal. Sign up for Dispatches to get stories like this one as soon as they are published.

This article contains descriptions of threats of violence and mental illness.

This article was produced for ProPublica’s Local Reporting Network in partnership with Mississippi Today. It was also co-published with Sun Herald and Northeast Mississippi Daily Journal. Sign up for Dispatches to get stories like this one as soon as they are published.

Agnel Philip contributed reporting.

Agnel Philip contributed reporting.